|

Associated

Oil Bridge Construction Folio – 1935

Bonds

to Finance Proposed Golden Gate Bridge – 1930

Photo:

USS California Passes Under the Golden Gate Bridge

Photo:

Pan-American Clipper Passes Over the Golden Gate Bridge

Photo:

Construction of the Golden Gate Bridge South Tower

Photo:

Joseph Strauss and the Golden Gate Bridge Designers – 1930

Bay

Bridge Smashups Spur Planning Conference -1940

16 Views of GG Bridge Construction - PowerPoint 764K

Story

Behind Building the Golden Gate Bridge

Toll

Rates and General Bridge Rules — 1937

Purchase

a Golden Gate Bridge Print

Purchase an

Authentic Golden Gate Bridge Rivet

|

Symphonies

in Steel:

Bay Bridge and the Golden Gate

By John Bernard

McGloin, S.J.

Professor of History

University of San Francisco

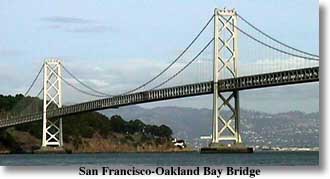

San Francisco

can rightly claim to be one of the skyline cities of the nation. Situated

at the tip of a peninsula and built in considerable part upon hills, the

city is surrounded on three sides by the waters of the Golden Gate, the

bay, and the Pacific Ocean. From the air, one notices a thread leading

eastward across the Bay, and another leading northward across the Golden

Gate. These two threads are, of course, two of the truly great bridges

of the world: the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, opened in late

1936, and the Golden Gate Bridge, opened the following summer.

A plaque

is located at the southeastern corner of Montgomery and Jackson streets

in San Francisco; the text of the inscription reads as follows:

On this

site the first San Francisco Bridge was constructed in 1844 by order of

William Sturgis Hinkley, Alcalde of Yerba Buena. It crossed a creek which

connected Laguna Salada with the Bay and was regarded as a remarkable structure

and great public improvement as it shortened the distance to the town’s

Embarcadero at Clarke’s Point.

San Francisco

and adjacent areas have come a long way in the matter of bridges since

the Hinkley span. Within the 450 square miles of landlocked harbor, San

Francisco Bay has eight major highway bridges, including four of the world’s

greatest steel bridges, as well as two railroad bridges. Four of these

bridges, San Francisco-Oakland, Golden Gate, Richmond-San Rafael,

and Carquinez Straits, are rated among the ten most notable structures

of their kind in the world. Other bridges include the San Mateo-Hayward,

Dumbarton, Southern Pacific’s Suisun Bay and Redwood City-Newark railroad

crossings, as well as the Antioch , Bridge. Easily the most important of

all these are the two bridges that were completed in 1936 and 1937.

Mention

was previously made of Emperor Norton; during his quixotic reign as “Norton

I, Emperor of North America and Protector of Mexico,” he issued

a “decree” that San Francisco Bay be bridged immediately. This was

to remain unfinished business until long after the emperor, as well as

his two dogs, Bummer and Lazarus, had retired from the civic scene. However,

when at length the emperor’s mandate was fulfilled, presumably even his

imperious self would have been satisfied.

The Bay Bridge

is the longest steel high-level bridge in the world. As mentioned

earlier, the Yerba Buena Tunnel with its diameter of 58 feet, which forms

part of the highway between San Francisco and Oakland, is the tallest bore

in the world. Additionally, the Bay Bridge can boast of the fact that its

construction required the greatest expenditure of funds ever used for a

single structure in the history of man. Its foundations extend to the greatest

depth below water of any bridge built by man; one pier was sunk at 242

feet below water, and another at 200 feet. The deeper pier is bigger than

the largest of the Pyramids and required more concrete than the Empire

State Building in New York.

The Bay Bridge

is the longest steel high-level bridge in the world. As mentioned

earlier, the Yerba Buena Tunnel with its diameter of 58 feet, which forms

part of the highway between San Francisco and Oakland, is the tallest bore

in the world. Additionally, the Bay Bridge can boast of the fact that its

construction required the greatest expenditure of funds ever used for a

single structure in the history of man. Its foundations extend to the greatest

depth below water of any bridge built by man; one pier was sunk at 242

feet below water, and another at 200 feet. The deeper pier is bigger than

the largest of the Pyramids and required more concrete than the Empire

State Building in New York.

On Thursday,

November 12, 1936, at 12:30 p.m. the Bay Bridge was opened to vehicular

traffic; its construction had continued for exactly three years, four months,

and three days. It was the result of years of discussion and planning on

the part of those concerned with providing means of transportation other

than by ferry between San Francisco and the East Bay. The Hoover-Young

Bay  Bridge

Commission (named after President Hoover and California’s Governor C.C.

Young) began sessions in Sacramento in October 1929. With the cooperation

of various state agencies, an engineering and traffic study was made. Finally,

the present route was agreed upon and the considerable financing of the

project was explored. As finally constructed, the Bay Bridge is 43,500

feet or 8 1/4 miles long, from end to end of the approaches. The bridge

proper, including the Yerba Buena crossing, is 23,000 feet or 4 1/2 miles

long. On the San Francisco side of Yerba Buena Island, the structure consists

of two complete suspension bridges with a central anchorage in the middle.

The towers of the suspension rise 474 and 519 feet above water. Over the

east channel, the span continues with one main cantilever span of 1,400

feet and, east of this, five truss spans each measuring 509 feet. The two

cables supporting the suspensions are each 28 3/4 inches in diameter, and

each contains 17,664 wires; the total length of these wires is 70,815 miles,

which is enough to encircle the earth three times. The concrete and steel

used in building the Bay Bridge would build thirty-five San Francisco

Russ Buildings plus another thirty-five Los Angeles City Halls or

L.C. Smith buildings in Seattle. Each of the two principal towers represents

a construction job equivalent to building a sixty-story skyscraper. Bridge

Commission (named after President Hoover and California’s Governor C.C.

Young) began sessions in Sacramento in October 1929. With the cooperation

of various state agencies, an engineering and traffic study was made. Finally,

the present route was agreed upon and the considerable financing of the

project was explored. As finally constructed, the Bay Bridge is 43,500

feet or 8 1/4 miles long, from end to end of the approaches. The bridge

proper, including the Yerba Buena crossing, is 23,000 feet or 4 1/2 miles

long. On the San Francisco side of Yerba Buena Island, the structure consists

of two complete suspension bridges with a central anchorage in the middle.

The towers of the suspension rise 474 and 519 feet above water. Over the

east channel, the span continues with one main cantilever span of 1,400

feet and, east of this, five truss spans each measuring 509 feet. The two

cables supporting the suspensions are each 28 3/4 inches in diameter, and

each contains 17,664 wires; the total length of these wires is 70,815 miles,

which is enough to encircle the earth three times. The concrete and steel

used in building the Bay Bridge would build thirty-five San Francisco

Russ Buildings plus another thirty-five Los Angeles City Halls or

L.C. Smith buildings in Seattle. Each of the two principal towers represents

a construction job equivalent to building a sixty-story skyscraper.

The chief

engineer for the entire project was Charles H. Purcell (1885-1951) whose

competency was matched only by his modesty. Assisting him was Charles E.

Andrew as bridge project engineer and Glen Woodruff as designer. Total

cost of the bridge, including interurban electric rail facilities (since

unfortunately abandoned), amounted to $79.5 million. This was financed

by sale of 4 and 3 percent revenue bonds, which were purchased by the Federal

Reconstruction Finance Corporation. In addition to these bonds, the California

State Gas Tax Fund loaned $6 million for the building of the approaches;

both sums were eventually repaid from toll revenues. (In 1958, a

four-year

reconstruction program was undertaken at a cost of $35 million.) Decreasing

patronage of the interurban trains had caused the Key System Lines to abandon

this service, leaving buses to handle the load exclusively. This reconstruction

involved track removals, conversion of each deck (lower and upper) to one-way

motor vehicle traffic, and the lowering of the lower deck of the bridge

by 16 inches through the Yerba Buena Tunnel. The maintenance of such a

colossal structure keeps a legion of persons constantly at work. No matter

from what angle the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge is viewed, it

will always remain a symphony in steel.

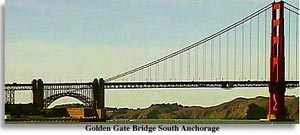

For years,

the Golden Gate Bridge held the title of longest suspension bridge in the

world. Despite the claims that the Mackinac span, which connects the greater

part of Michigan with its upper peninsula across the Straits of Mackinac

is longer, the question is best resolved by settling what is meant, indeed,

by “longer”: actually, the Mackinac suspension is supported by a single

span of cables 8,344 feet in length as compared with 4,200 for the Golden

Gate Bridge. However, the center span of the Mackinac Bridge is exceeded

in length by both the Verrazano Narrows Bridge in New York City and the

Golden Gate Bridge. The claim of “longest” for the Mackinac is based upon

the distance between cable anchorages, while the Golden Gate figure is

based upon the actual distance between its towers. Rival claims, though,

do not seem to be of great importance, since all will admit that, just

as is true of its sister span across San Francisco Bay, the Golden Gate

is “quite a bridge,” the fulfillment of a dream and a vision had by one

man: it is the “bridge that couldn’t be built.”

Triumphantly,

then, on Thursday, May 27, 1937, San Franciscans joined other thousands

in walking across the newly opened Golden Gate Bridge, all together a huge

throng of approximately 200,000. This “preview” was followed the next day

by dedicatory ceremonies which culminated in the cutting of a ceremonial

barrier, after which an official cavalcade of automobiles traversed the

span; the rest of that day was devoted, again, to pedestrian traffic, and

the regular flow of vehicular traffic started the next day. It has been

written that

Triumphantly,

then, on Thursday, May 27, 1937, San Franciscans joined other thousands

in walking across the newly opened Golden Gate Bridge, all together a huge

throng of approximately 200,000. This “preview” was followed the next day

by dedicatory ceremonies which culminated in the cutting of a ceremonial

barrier, after which an official cavalcade of automobiles traversed the

span; the rest of that day was devoted, again, to pedestrian traffic, and

the regular flow of vehicular traffic started the next day. It has been

written that

Residents

of the San Francisco Bay area feel this bridge as an entity and have a

section for it. They admire its living grace, and its magnificent setting.

They respond to its many moods—its warm and vibrant glow in the early

sun, its seeming play with, or disdain of, incoming fog, its retiring shadowy

form before the sunset, its lovely appearance in its lights at night. To

its familiars it appears as the “Keeper of the Golden Gate.”[l]

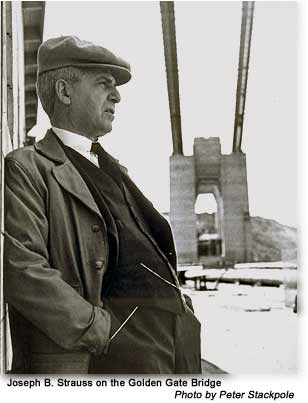

The Golden

Gate Bridge is the result of the long-term determination of the

people of six California counties who, eventually, formed themselves

into a Golden Gate Bridge District comprising the city and county of San

Francisco, Marin, Sonoma, and Del Norte counties, as well as a portion

of Napa and Mendocino counties. Since it had long been apparent that the

bridging of the Golden Gate, despite the many problems its construction

would entail, would mean an effective opening up of the counties north

of San Francisco, much planning went into the implementation of the visions

and dreams of the members of the Bridge District. In 1928, earlier efforts

culminated in the incorporation of the Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District;

in November 1930, the voters of the concerned counties passed a $35 million

bond issue to finance the building of the bridge, while pledging the property

of these counties as security for the payment of the bonds. For many years,

Joseph Baerman Strauss (1870-1938), a distinguished engineer with many

bridges to his credit, had dreamed of raising a span across the Golden

Gate. One who contemplates his many activities realizes that Strauss was

much more than merely a competent structural engineer, although he certainly

was that: he was also a poet, a seer, and a man of vision and it seems

that all these qualities sustained him in the fulfillment of his dream;

it is equally certain that he had to live with the skepticism of his peers

who kept repeating that “Strauss will never build his bridge, no one can

bridge the Golden Gate because of insurmountable difficulties which are

apparent to all who give thought to the idea.” But Strauss held fast to

his vision, and, even though he survived only a year after the opening

of his bridge, he did live to bring it to completion.[2]

Construction

of the bridge took four and one-half years and the work began on January

5, 1933. The resulting span has been much admired for its magnitude and

its graceful beauty. At mid-span the bridge is 220 feet above the

waters of the Golden Gate; it is about a mile across and there is only

one pier in the water which, incidentally, was built under most discouraging

circumstances, as Engineer Strauss could testify. This pier is only 1,125

feet from shore; the distance between the two towers that support the cables

which, in turn, support the floor of the bridge, is 4,200 feet. These two

cables are 361/2 inches in diameter, the largest bridge cables ever made.

Each cable is 7,659 feet long and contains 27,572 parallel wires, enough

to encircle the world more than three times at the equator. Fortunately,

solid rock was found at each end of the Gate and huge pockets were excavated

in this rock to form a setting for the concrete anchorage blocks, each

of which contains 30,000 cubic yards of concrete. Among the engineering

problems that had to be faced in the building of the bridge were those

that arose from the exposed nature of any such structure, for it has to

withstand winds and gales coming from the often far from peaceful Pacific

Ocean. It was so designed that, in the most unlikely event of a broadside

wind coming at it with a speed of one hundred miles an hour, the bridge

floor at mid span might swing as much as 27 feet.[3] Construction

of the bridge took four and one-half years and the work began on January

5, 1933. The resulting span has been much admired for its magnitude and

its graceful beauty. At mid-span the bridge is 220 feet above the

waters of the Golden Gate; it is about a mile across and there is only

one pier in the water which, incidentally, was built under most discouraging

circumstances, as Engineer Strauss could testify. This pier is only 1,125

feet from shore; the distance between the two towers that support the cables

which, in turn, support the floor of the bridge, is 4,200 feet. These two

cables are 361/2 inches in diameter, the largest bridge cables ever made.

Each cable is 7,659 feet long and contains 27,572 parallel wires, enough

to encircle the world more than three times at the equator. Fortunately,

solid rock was found at each end of the Gate and huge pockets were excavated

in this rock to form a setting for the concrete anchorage blocks, each

of which contains 30,000 cubic yards of concrete. Among the engineering

problems that had to be faced in the building of the bridge were those

that arose from the exposed nature of any such structure, for it has to

withstand winds and gales coming from the often far from peaceful Pacific

Ocean. It was so designed that, in the most unlikely event of a broadside

wind coming at it with a speed of one hundred miles an hour, the bridge

floor at mid span might swing as much as 27 feet.[3]

Practically

all of the Golden Gate Bridge is located within the city and county of

San Francisco (as is the Golden Gate itself). The two towers rise an impressive

746 feet which means that they are 191 feet taller than the Washington

Monument. In 1884, a poet thus saluted the Golden Gate:

Wide Thy

Golden Gate stands open to all

Nations of the world,

Free beneath its stately portals

All flags are in peace unfurled.

Beauteous Gate, when loitering Sunset

Covers Thee with burnished gold.

Mighty Gate, when surging ocean Thy

Strong cliffs alone withhold.

Treacherous

Gate, deceiving many with a

Name most fair-Blessed Gate, where millions

Find the golden boon of liberty. [4]

|

At the completion

of his mighty bridge, Joseph Strauss penned an impressive ode which he

entitled “The Mighty Task Is Done”; it epitomizes his personal travail

in building the bridge and makes of the structure almost a living thing.

From his poem, these lines give evidence of the dedication of the man who

brought the bridge from his brain and heart as well as from his drawing

board:

At last

the might task is done;

Resplendent in the western sun;

The Bridge looms mountain high

On its broad

decks in rightful pride,

The world in swift parade shall ride

Throughout all time to be.

Launched

midst a thousand hopes and fears,

Damned by a thousand hostile sneers.

Yet ne’er its course was stayed.

But ask of those who met the foe,

Who stood alone when faith was low,

Ask them the price they paid.

High overhead its lights shall gleam,

Far, far below life’s restless stream,

Unceasingly shall flow....

|

With the

completion of the two giant bridges, it was but natural that a proud San

Francisco would again wish to call the people of the world to itself; so

it was that another world fair, this one called the Golden Gate International

Exposition, was planned and brought into being. Several years previously,

a movement to develop an airport site by constructing a fill over the shoal

area adjacent to Goat Island (Yerba Buena) was started. Although the airport

was finally placed elsewhere, the planning resulted in a man made island

(called “Treasure

Island”) on which was staged the exposition.

When the

voters of San Francisco decided to have such an exposition, the question

of financing the necessary engineering work was happily resolved. In late

1935, the city of San Francisco succeeded in having the project approved

as a Works Progress Administration (WPA) project. This authorization, including

20 percent to be furnished by San Francisco, amounted to $3,803,900. After

further study, the WPA concluded that the nature of the work required was

such that it could not handle the project. The Secretary of War approved

the request that its execution be undertaken by the Army Corps of Engineers.

While a group of such specialists applied their talents to the reclamation

of the “Yerba Buena Shoals,” the day-by-day details were efficiently

cared for by Colonel Fred Butler, U.S.A., who had years of army engineering

experience behind him at this time. The fill to form Treasure Island was

obtained by dredging operations; the island covered an area of 400 acres,

5,520 feet long by 3,410 feet wide.

Meanwhile,

the San Francisco Bay Exposition Company was formed with Leland W. Cutler

as president. He was greatly aided from the beginning by George Creel,

who was appointed United States Commissioner of the Exposition. By 1938,

1,200 men were employed in horticultural work on the newly born Treasure

Island; they planted 400,000 bulbs, 800,000 seeds, and 4,000 trees. It

then remained for the architects and artisans to accomplish their respective

tasks. The international dimension came only gradually as Leland Cutler

persuaded those concerned that an invitation should be extended to other

countries to join in the celebrations. A subtitle, “A Pageant of the Pacific,”

was added to the title of the exposition, and gradually its international

status was assured.

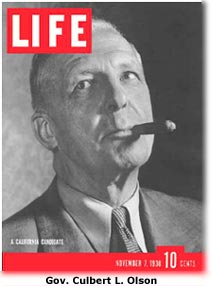

On Monday,

February 18, 1939, the “Magic Isle” as many called it, was opened to an

expectant public; special ceremonies were presided over by Governor Culbert

C. Olson who appeared before a decorative Golden Gate Bridge portal to

the exposition armed with a large key. With the opening of this portal,

the exposition commenced. Although not all the exhibition halls had yet

been completed, there were enough attractions, plus the novelty of the

site itself, to satisfy those who thronged the island on opening day. Notable

were the Tower of the Sun with its Elephant Towers, while many came to

regard the Federal Building as the most striking of all the buildings.

The landscaping and horticultural results attracted much favorable comment.

The extensive art work also merited approval; among the best murals were

those of Millard Sheets depicting California history. These were supplemented

by some borrowed European masterpieces. When one added to the above features

the scientific exhibits and recreational areas, it was apparent that there

was “something for everyone” in the Golden Gate International Exposition.

During its run, the exposition attracted 17 million visitors. However,

it was not a financial success; in October 1939, the Pageant of the Pacific

closed its gates, six weeks early and $4,166,000 in debt. It was decided

to reopen the exposition in 1940 in the hope of recouping these financial

losses. This was done in the spring of 1940 when Europe was in the convulsions

of war. However, the Fair went on as planned; when it finally closed its

doors in September 1940, an admirer wrote:

On Monday,

February 18, 1939, the “Magic Isle” as many called it, was opened to an

expectant public; special ceremonies were presided over by Governor Culbert

C. Olson who appeared before a decorative Golden Gate Bridge portal to

the exposition armed with a large key. With the opening of this portal,

the exposition commenced. Although not all the exhibition halls had yet

been completed, there were enough attractions, plus the novelty of the

site itself, to satisfy those who thronged the island on opening day. Notable

were the Tower of the Sun with its Elephant Towers, while many came to

regard the Federal Building as the most striking of all the buildings.

The landscaping and horticultural results attracted much favorable comment.

The extensive art work also merited approval; among the best murals were

those of Millard Sheets depicting California history. These were supplemented

by some borrowed European masterpieces. When one added to the above features

the scientific exhibits and recreational areas, it was apparent that there

was “something for everyone” in the Golden Gate International Exposition.

During its run, the exposition attracted 17 million visitors. However,

it was not a financial success; in October 1939, the Pageant of the Pacific

closed its gates, six weeks early and $4,166,000 in debt. It was decided

to reopen the exposition in 1940 in the hope of recouping these financial

losses. This was done in the spring of 1940 when Europe was in the convulsions

of war. However, the Fair went on as planned; when it finally closed its

doors in September 1940, an admirer wrote:

Before we

expected it, the day came to close the gates. It was a sad occasioned especially

for the rest of us who had found refreshment on Treasure Island. When the

final bills had been paid, it would be recorded that the Golden Gate International

Exposition, like so many others before and since, had lost money. The staff

compiled a final report, cleaned out the files and drifted away. [5]

Today Treasure

Island is owned by the Navy. After Pearl Harbor, the site was turned

over to the federal government by San Francisco and it is now one of

the West Coast’s main naval installations. Three of the expositions’ permanent

buildings are used by the Navy.

NOTES

AND SOURCES

Sources

While journalistic

sources are abundant for both bridges, neither has yet had as complete

accounts as they deserve. On the Bay Bridge, cf.

The San Francisco-Oakland

Bay Bridge (no author indicated, Chicago, 1936). On the Golden Gate

Bridge, best so far is Allen Brown, Golden Gate: Biography of a Bridge

(New York, 1965). On the Golden Gate International Exposition which celebrated

the completion of both bridges, cf. Richard Reinhardt, Treasure Island:

San Francisco’s Exposition Years (San Francisco, 1973).

Notes

I. These

appreciative words are in a mimeographed release published by the Golden

Gate Bridge District (no date, no author indicated) which contains much

information about the bridge.

2. Appropriately,

Strauss’s statue has been erected in an area close to the bridge. The inscription

reads as follows:

|

1870—

Joseph B. Strauss—1938

"The Man who Built the Bridge."

Here at the Golden Gate is the

Eternal Rainbow that he conceived

And set to form, a promise indeed

That the race of man shall

Endure unto the Ages.

Chief Engineer of the Golden Gate Bridge 1929-1937

|

3. A dramatic

test, which the Golden Gate Bridge passed successfully, came on Saturday,

December 1, 1951. Between 5:55 P.M. and 8:45 P.M. the bridge was closed

to traffic because of a violent storm which generated a gale with a velocity

of seventy miles an hour. The deck of the bridge swayed twenty-four

feet from side to side and five feet in the perpendicular dimension. Since

the bridge was designed to sustain a twenty-seven-foot sway,

no serious effects came from this dramatic moment. Close examination of

the structure later indicated only minor damage.

4. Poem:

“Mission Dolores” in A California Pilgrim (no author indicated,

San Francisco, 1884) p. 114.

5. The

Great Exposition; in the San Francisco Chronicle, October 14,

1973. The article is an adaptation of his book, Treasure Island

(San Francisco, 1973).

IN: San

Francisco, the Story of a City, by John Bernard McGloin. San Rafael,

Calif. : Presidio Press, 1978.

Return

to the top of the page.

|